I wrote on my Rational Transport policy blog on this topic, largely because it was around transport governance issues. The article is here.

Friday 16 February 2024

Wednesday 31 January 2024

Don't make road pricing a tool in a "war on cars"

The BBC website, under its “Future Planet” science-based section, published an article on 23 January 2024 called “From London to New York: Can quitting cars be popular?” It has received quite a bit of acclaim, but although the article does make a case for the benefits of reducing car traffic in major cities, it is largely one-sided in a way that, largely, “preaches to the choir” about a wide range of policy measures with the objective of making driving less attractive in cities.

Road pricing is a powerful policy tool that can significantly improve the efficiency and the environmental impact of a road network, as well as providing an efficient way to fairly recover the costs of capital and maintenance of the network and ensure demand does not overwhelm supply. It can also generate net revenues for improvements, or simply net revenues as a return on the capital tied up in the network, for complementary purposes, such as improving infrastructure for alternatives.

However, undoubtedly the biggest barrier to implementation of road pricing is concern that it is a tool to penalise and punish, or to tax, rather than a tool to deliver better outcomes for those who choose to pay, as well as those who benefit from less congestion and well-maintained roads. This includes those riding buses on them, walking, cycling and those who live, work or own businesses, or community facilities adjacent to roads. It is extraordinarily difficult to convince the public and as a result, many politicians, that any form of road pricing should be introduced, because many don’t believe there are benefits to them from pricing roads. It is difficult enough to convince people that electric cars should pay a distance-based road user charge, because they are not subject to fuel tax, let alone convince people to pay governments to use roads directly.

This article doesn’t help in changing that perception.

There are real perceptions about a war on cars, the article cites someone who produces a podcast called “War on Cars”, so it isn’t entirely a conspiracy theory. There have long been policies to discourage car use in cities, whether it is removal or caps on parking, slower speed limits, traffic light phasing or reducing road capacity. Road pricing can have a range of objectives, but to treat it only as a tool to reduce driving, rather than also a tool to improve the conditions for those who remain on the road, is a mistake.

There are precious few congestion pricing systems in operation around the world. In Europe there remain only five cities of scale with congestion pricing: London, Stockholm, Gothenburg, Milan and Olso although plenty more have investigated it (and a few Norwegian cities with toll rings that exist primarily to raise revenue). Abu Dhabi, Doha and Dubai all have pricing systems, and further east is Singapore. New York will be the first in the US, but Lower Manhattan is very different from pretty much any other urban area in the US.

The reason for this is public opposition.

It’s absolutely true that after pricing is introduced it generally gains better acceptance, as sceptical drivers notice that the impacts are not bad, and in some cases improve conditions. This is certainly the experience in London and Stockholm, although it was not the experience in Gothenburg, because Gothenburg’s congestion tax was applied far too broadly, in geographic and temporal terms (to locations at times where/when there was no congestion). Opposition after it was introduced persisted for some years. A referendum held a year after it was introduced in 2013 saw 57% oppose it, but it was ignored as local politicians had committed to spending the revenue on large projects (and there was no other means to pay for them).

The article quotes Leo Murray, director of innovation at climate charity “Possible” saying “We can't find a single example of a traffic-reduction measure that's been in place for more than two years that's then gone on to be removed because of a lack of public support”.

Well, I can. It’s the Western Extension of the London Congestion Charge. It was introduced in 2007 and removed at the end of 2010. It was removed because it was poorly designed (it granted residents in one of the wealthiest parts of London a 90% discount for driving into the central zone), poorly focused and implemented for partisan political reasons (the Mayor of London wanted to target a wealthy area, but perversely gave them discounts to drive to the centre of London that poorer area residents did not have).

So, in short, you can’t just introduce road pricing and assume the public will accept it. Note the Stockholm congestion tax referendum is cited as giving its scheme approval, but in fact the referendum was held across many municipalities across metro Stockholm, where a majority voted against the congestion tax, and it was only by ignoring those other municipalities that it was said that the majority voted for the congestion tax. Stockholm Municipality voted for it, but only consists of 38% of the population of metro Stockholm. Had the votes in all Stockholm municipalities been taken into account, it would have been a vote of 52.5% against road pricing.

Again, the article seems to be dismissive of how hard road pricing is to introduce.

The article returns to London with the correct point that the congestion charge was more popular after it was introduced, but with the closure of the Western Extension, the congestion charge in London has the same geographic scope as it had when it was introduced in 2003, which is roughly 1% of the area of metropolitan London. It hasn’t expanded because there isn’t the political will or public support, in no small part because congestion in central London has essentially returned to pre-congestion charge levels. It is difficult to convince the public that expanding the congestion charge will reduce congestion, when the existing charge has not kept up with demand, and when significant amounts of road capacity is reallocated from general traffic to cycling and walking capacity. London was a success, but why has no other UK city (Durham doesn’t count in this context) have a congestion charge? It’s fairly basic – too many of those advocating for it, don’t want to deliver any benefits to those who would pay it. Furthermore, it’s simply wrong to cite the ULEZ expansion and ignore the significant opposition to it.

New York’s implementation of the Central Business District Tolling Program is cited as a key example, and questions whether New York has learned from elsewhere, although it is a stretch to call it congestion pricing. The article says “The scheme will also operate a fluctuating charge system, with smaller fees during off-peak hours, providing flexibility”. The charges don’t “fluctuate” unless it is meant that they have just two time zones over a 24 hour period (which are different during weekend. Off-peak is… 2100-0500 weekdays. Unless you are currently driving around 2000 or 0530, you probably don’t think this is “flexible”. The London Congestion Charge has shorter operating hours, and although it is a flat fee, 0700-1800 weekdays provides a bit more flexibility to avoid it.

Its program is designed primarily to raise revenue for the ailing subway network, which is desperately in need of capital renewal. Reducing congestion and emissions matter, but it has been designed, in terms of hours of operation and scope, to raise money. This is all very well, but lower Manhattan is hardly translatable to most other cities in the USA. I’m sceptical as to whether it will generate more than some more studies in the next five years, just because of the tendency of many engineering consultancies to simply look to “copy and paste” what is done in another city onto whatever city they are commissioned to study. That would be a mistake and would take road pricing backwards in any city that simply commissions a quick study from people with no experience on the topic, to just “do a New York”. This is what happened in the UK for a few years after London (although Manchester had quite a different scheme design), and nothing came of it.

The BBC article goes off-topic when it claims Oregon is “considering following suit”, by saying it is testing a “more extensive system” based on vehicle-miles travelled. No it is not. This is the OReGO program, which is testing road usage charging (RUC) as a way of charging electric and other ultra-fuel efficient motor vehicles to use all public roads in Oregon, as a replacement of state fuel taxes. It is absolutely not planned to reduce car traffic, and is not focused on cities. It is about sustainable and fair charging of light vehicles to pay to maintain the road network, and it is really important to keep these objectives distinct and different.

I hope New York can spur wider interest in the US for congestion pricing, and not on the basis of overly simplistic drawing a cordon around a downtown area. There are a range of different solutions, depending on the definition of the problem, but regardless of what is considered, it is extraordinarily difficult to get social licence, so to speak, for congestion pricing when a key objective is not to reduce congestion and improve travel times for those that are expected to pay.

In that context the global examples worth citing as success stories are Singapore, Stockholm and the evolution of the Oslo toll ring to a congestion charge. London as a success story lasted around five or so years. The world is littered with studies that went nowhere. Hong Kong has been studying congestion pricing for nearly 40 years, Copenhagen, Helsinki and the Netherlands more generally have tried and failed due to public opposition. Consider that many would perceive those cities (and country) to have enviable standards of public transport, and levels of cycling, and it is still difficult.

Congestion pricing can deliver so many potential benefits for cities, firstly by freeing up sclerotic networks that drag productivity and efficiency down, by adding to the cost of freight and the cost of services needed to make cities function. So much is invisible, because it is not delivered by government, but electricians, plumbers, builders, painters, tilers etc, all can do less at higher cost, because of congestion, and almost none of them have any modal choice. Road freight supplies the food, the clothing, the consumables (toilet paper!), the appliances and building materials that keep people alive and keep infrastructure maintained. Then there are people who need cars for specific trips, either because of where they are going or what they are carrying, or more generally there is urgency in a trip, such as for medical purposes or an urgent appointment, or a flight. Big cities work well with all modes well catered for, and operating efficiently, but buses can't always have their own lanes, and get caught up in traffic.

Roads that enable traffic to flow efficiently help all of this, they also help contain emissions by not wasting fuel on either idling or erratic stop/start movements (this includes EVs), and improve access, as gridlocked streets hinder everyone (let alone emergency services from time to time). It is entirely understandable and logical to seek to reduce car traffic on some city streets, because of how space inefficient they are, but cars have their place. In central London many users of the congestion charge are occasional drivers, on one-off trips for any variety of reasons (e.g., medical appointment, collecting a purchase) and the use of taxis and rideshare services reflects demand that is met by more car use elsewhere. Road pricing can deliver significant modal shift and can reduce travel demand, but in doing so it shouldn't be seen as a tool to punish drivers, but just the application of a concept (price) to an underpriced and scarce resource - road space.

While I always encourage those seeking to promote road pricing, the record of the past 25-30 years (since technology has made electronic pricing feasible) is that it is very difficult to implement because of public acceptability. Seeing it or promoting it as a tool to wage “the war on cars” just makes that even more difficult.

Wednesday 24 January 2024

Iceland and New Zealand: The first two countries to mandate road user charging for EVs

After many many years of others talking about it, one country has done it and another will soon follow. On 1 January 2024, Iceland introduced mandated road user charging (RUC) for electric vehicles (EVs), Plug-In Hybrids (PHEVs) and Hydrogen powered vehicles, and from 1 April New Zealand will also do so for EVs and PHEVs.

Iceland

Iceland has launched EV RUC with a website called "Our Roads to the Future". No later than 20 January 2024, eligible vehicles are required to have had their odometers read and recorded and transmitted to a government website or via a specific app. Those unable to use websites can go to an authorised service centre for an official reading.

The website indicates that the average petrol powered car pays ISK178,000 a year to use the roads (~US$1305) so the rate for EVs and hydrogen powered vehicles will be ISK6/km (US$0.044/km or US$0.07/mile), and for PHEVs at ISK2/km (US$0.015/km or US$0.024/mile). The lower fee for PHEVs reflect that they are still paying fuel excise for the use of petrol. Iceland presumably calculating that around two-thirds of kms driven by PHEVs is powered by petrol.

Iceland has indicated that this is a first step towards phasing out fuel taxes as a means of charging for road use, with the intention that RUC apply to all vehicles from 2025 (a distance-based tax already applies to some heavy vehicles).

The reason given is the growing proportion of EVs and PHEVs in the vehicle fleet as illustrated by the graph below:

|

| Proportion of private car fleet in Iceland with EVs or PHEVs |

Furthermore, Iceland reports a 50% increase in distance travelled on its roads between 2012 and 2022, including a 36% increase in the number of registered cars. On average vehicles are paying 30% less per vehicle in 2022 compared to 2012, because of the rise of EVs and PHEVs, as well as the emergence of more fuel efficient vehicles generally.

In Iceland each vehicle owner will be invoiced monthly for distance travelled, which will be estimated based on the national average, until another odometer reading is reported after one year. After that point motorists will be expected to supply more regular odometer readings.

Of interest is that the Icelandic Government has estimated that even after introduction of RUC, it will still be around ISK160,000 (US$1173) less per annum to drive an EV compared to an ICE vehicle, so that the impact of RUC on purchases of such vehicles is expected to be minimal.

Some interesting stats from Iceland include:

- 75% of owners of EVs and PHEVs are located in Reykjavik compared to 64% of the population

- 64% of EV and 61% of PHEV owners are in the top three income deciles

- The highest distances travelled by residents are in those located in municipalities immediately surrounding the Reykjavik metro area, lowest by those in more rural areas. This contradicts some concerns that distance-based charges would unfairly penalise those in rural areas.

Tuesday 23 January 2024

Does London's ULEZ expansion help or hinder better road pricing in the UK?

|

| Greater London Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) coverage area |

To say that the Mayor of London's expansion of the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) to all of the territory of greater London under his authority has been controversial is an understatement. For some it is a necessary response to climate change and the effects of local air pollution on public health, for others it is an impost on those who cannot afford a newer vehicles with benefits that are questionable, given that most vehicles comply with it already (hence it cannot have much of an impact). Even Leader of the Opposition, Labour Leader Sir Keir Starmer has refused to back it.

The ULEZ started by being parallel to the London Congestion Charge in inner London, was expanded to the A406/A205 North and South Circular Roads. Its coverage of all of London includes rural areas and rural roads, as well as outer suburbs.

For a start it is important to be clear that the ULEZ is not road pricing. It is fundamentally a regulatory instrument that requires permits for vehicles that do not comply with the zone, in order to enter or drive within it. There is no relationship between the ULEZ and either the costs of providing road infrastructure or demand for it. The fee is set at a level to dissuade use and generate revenue, and it is blunt. It doesn't matter if you drive a EURO 0 diesel van in crawling traffic beside a school or a EURO 3 petrol car at 3am on the motorway like A12 East Cross Route, you pay the same, even though objectively the local air quality impact is vastly different. Although a vehicle scrappage scheme has been set up in parallel, owners of vehicles outside London are not eligible even though many cross into the zone. Some categories of vehicles have exemptions, such as historic vehicles (e.g., vehicles built before 1973) vehicles registered to carry disabled people (until 24 October 2027), wheelchair accessible vehicles, drivers on specific disability benefits. Those travelling to hospital appointments deemed unfit to use public transport can also apply for a refund.

Vehicle scrappage scheme

All London residents can apply for up to £2,000 for scrapping a car or up to £1,000 for scrapping a motorcycle. For wheelchair accessible vehicles there is a payment of £10,000 to scrap or £6,000 to retrofit to the ULEZ standards. The scrappage scheme has been claimed by over 37,200 individuals or entities, which has cost £120m. The total budget for the scheme is £160m. The biggest criticism of it, is that £2,000 will not come remotely close to buying a new vehicle, although it might come close to buying one that barely crosses the ULEZ standard. However, it is unclear if the ULEZ standard advances (so EURO 4 petrol cars are no longer compliant), if people who took the £2,000 for scrapping a non-compliant vehicle, can claim it again if their latest vehicle is also non-compliant.

ULEZ impacts

There are a range of claims about the impacts of the ULEZ.

Compliance rates for the ULEZ are reportedly 95% meaning the proportion of vehicles that meet the ULEZ standard. Of note, Heathrow Airport claims 7% of its employees drive non-compliant vehicles (and Heathrow is located just within the boundary of the ULEZ

The BBC claims this indicates revenue of around £23.6m per month. This is not inconsiderable, and certainly backs some claims that ULEZ is about revenue more than it is about environmental outcomes. Van compliance is much lower than the average, with around 86.2% compliance. However, City Hall claims it will generate no net revenue by 2026-2027, presumably as the costs of operating it are not exceeded by the fine and fee revenue generated (as it is expected few non-compliant vehicles will enter the zone).

One claim is that ULEZ will reduce the number of cars on London roads by 44,000. Fewer cars means some people won't own a car anymore, which reduces their mobility. For some, London's ample public transport network and expansion of cycleways provide alternatives that may be reasonable for most trips, with carshare schemes plugging the gap. If people choose to give up owning a car because the cost isn't worth the benefit, and alternatives meet their needs, that's all very well, but if they are choosing to give it up because of the cost of ULEZ makes it unaffordable, it is clearly a policy measure that is pricing poorer households out of car ownership (because wealthier ones can afford a car that meets the standard).

The Mayor of London has published a report on the first month after the introduction of the wider ULEZ. Its findings include:

- 77,000 fewer non-ULEZ compliant vehicles per month identified than before its expansion (a 45% reduction), with a reduction of 48,000 unique vehicles identified overall (which may indicate non-compliant vehicles not being used, but compliant vehicles may be used more in some cases).

- 96% of vehicles driving in Outer London meet the ULEZ standard (86% of vans).

- On an average day only 2.9% of vehicles driving in the ULEZ pay the charge, 1.7% are registered for a discount or exemption and 0.2% are issued a Penalty Charge Notice.

What isn't clear is the impacts on air quality.

What about road pricing?

Beyond extending the operating hours of the central London congestion charge, there has been no changes to policy on road pricing in London since 2011 when the Western Extension was scrapped. Mayor Sadiq Khan has claimed there are plans to introduce distance-based road pricing in London, according to the Evening Standard. Expanding road pricing in London has been discussed for some time, but it hasn't been advanced largely because:

- Nobody (since Ken Livingstone) has been willing to spend political capital on making a cogent and consistent argument for wider road pricing across London;

- The objectives of such a scheme have not been well defined. Mayor Khan's primary transport policy objective has been around local air quality, not congestion;

- The options for road pricing across London have a significant upfront cost (in roadside infrastructure and potentially in-vehicle technology);

- Central government has been keen to leave it as primarily a local matter, and for the Mayor of London and Greater London Authority to take the risk in advancing road pricing, rather than lead from Westminster.

- Zonal based boundaries, pricing for driving across parts of London (but not within zones). This would have the advantage of being relatively simple to understand, but would significantly disadvantage people and businesses needing to drive across multiple boundaries. In particular, businesses located adjacent to a boundary may feel aggrieved if part of their customers face a charge, which their rivals on the other side of the boundary do not.

- Distance, time, location based pricing. This is considered by some to be the best option because it offers unparalleled flexibility, and can address issues such as "rat-running" and can be set up to encourage more use of arterial routes over local roads.

Tuesday 21 November 2023

Auckland's Mayor and Council vote overwhelmingly for congestion charging, but there are some issues

The big road pricing news in New Zealand in the past week was the Mayor of Auckland, Wayne Brown, calling for congestion charging and appearing on media declaring how critical it was for the city. This was not in terms of raising revenue, but in addressing congestion. On Radio NZ he said Auckland could not afford another motorway, and that the charge would be avoidable by driving outside of peak times.

“I am of the view that this should be on our motorways in the central areas of Auckland, which are the most congested, and this is also where public transport works best, which gives some people an option rather than paying the charge”

He ridiculed concerns about equity around trade businesses, saying that to pay $5 to save 20 minutes was a small fraction of the price the tradespeople charge their customers in an hour. He also said that schoolchildren “don’t’ have a right to be taken to school in a BMW” and more should walk, bike or use public transport.

The Mayor was elected in 2022 and has a three year term, but his support for the concept was only solidified when Auckland Council voted 18-2 in favour of setting up a team to oversee implementation of congestion charging.

Despite that report, Auckland is not going to get congestion pricing in two years. Legislation will take around a year to introduce and pass at best, and it will take around 18 months to procure and install a system at best. However, you have to admire the ambition.

The astonishing level of local political support for the concept is unheard of in any other city where the private car is by far the dominant transport mode. In 2018 (according to the Census), around two-thirds of Aucklanders commuted by car (whether as driver or passenger), 11% by bus, 9% walked and 8% worked from home, 3% by train and just over 1% by bicycle. It seems likely that the proportion working from home, cycling and using public transport has increased since then.

Let's be clear to those unfamiliar with Auckland. The Mayor is ostensibly "centre-right" and got elected opposing the "war on cars". The Council as well is fairly balanced between left and right wing members.

Unlike New York and almost all other US cities that have been investigating congestion pricing, Auckland is regarding the net revenues as secondary (although the Mayor is interested in revenue, as the incoming government has pledged to abolish the regional fuel tax of NZ$0.10 per litre that raises revenue for transport projects in the city). The primary focus is reducing congestion and encouraging behavioural change. However, it would clearly generate net revenue and would also have positive environmental benefits.

Why does this matter?

All of the cities that have introduced congestion pricing around the world so far have been quite different from Auckland, and indeed all of the predominantly car-oriented low density cities that are seen in New World cities in New Zealand, Australia and North America. Singapore, Oslo, London, Stockholm and Milan all have significant mode shares for public transport. However, Dubai and Abu Dhabi (and soon Doha) are car dependent cities, even moreso than Auckland, whereas Gothenburg in Sweden is much closer to the mode shares seen in New World cities.

Although New York will be the first US city to introduce some form of congestion charging, it is being implemented in lower Manhattan, which is much more like central London than most US cities, and it is being introduced 24/7 (with peak charges) primarily to raise revenue. New York is not a model for other North American cities.

Auckland on the other hand, has around 87% of its employment outside the central city, it has around a 50% mode share for public transport and active modes for trips to the central city at peak times, but a much lower mode share for trips to other parts of Auckland at peak times. In short, congestion in Auckland is primarily about trips across the city, not to the downtown. Pricing in Auckland will work only in part by encouraging modal shift, but will in a large part be about encouraging a small proportion of trips to shift time of day or frequency of driving.

Furthermore, unlike many other developed cities, Auckland has had over 20 years of billions of dollars in continuous major capital spending on its transport networks. During that time, the road network has been significantly upgraded, with additional lanes on motorways and a ring route around the west bypassing the congested central motorway junction. The commuter rail network was extended to the downtown, electrified with new trains, adding new lines, and is now being expanded with an inner city loop. Bus services have been expanded, with busways and new buses, routes and expanded frequencies. In short, Auckland has seen extensive capital spending on its transport infrastructure and it has been unable to keep up with demand, and congestion has not been resolved.

Supply of transport infrastructure does not sustainably reduce traffic congestion.

If Auckland successfully implements congestion pricing, it will be a world leader in implementing road pricing in a city with automobile dominance.

What has been proposed?

The Mayor has specifically proposed a charge on two segments of motorway of NZ$3.50 - $5 per trip. It would operate in the AM and PM peaks only on the North Western Motorway (SH16) between Lincoln Road and Te Atatu Road, and on the Southern Motorway (SH1) between Penrose and Greenlane. These are two of the most congested parts of Auckland’s motorway network. The map below depicts the short section of North Western Motorway, the segment of Southern Motorway and the earlier proposed downtown cordon (which is bypassed by the motorway network which goes from south to the Auckland Harbour Bridge and from the west to the Ports of Auckland).

|

| Auckland congestion pricing concepts. |

Undoubtedly the motorway proposals would have a positive impact. While the North Western motorway at this location has no reasonable alternative route, the Southern motorway does have a wide at-grade arterial road, albeit with multiple sets of traffic signals and a much lower speed limit. Some measures would need to be taken to minimise diversion onto the parallel routes.

It's worth noting that a major study into congestion pricing in Auckland, called The Congestion Question, was carried out from 2016-2020, and recommended that a downtown cordon be introduced, followed by corridor charges on major routes in the isthmus and beyond. The Mayor is proposing the second stage, but that is good as the downtown cordon concept was likely to have a less dramatic impact than the proposed corridor charges.

The proposed technology would be automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) cameras.

What needs to happen?

- Don't see London as an example to copy. London is an area charge, it has a flat all day rate and has not enabled traffic to flow relatively efficiently for over 10 years because it is too blunt. London may be seen as culturally closest to Auckland, but it is vastly different. Better examples are in Singapore and Stockholm.

- Don't make this project about raising revenue. When the focus becomes revenue raising, the design will change and it becomes a lot more difficult to get the public on-board, because you are designing a tax, rather than a traffic management and pricing scheme.

- Don't make this about reallocating road space. While there will be localised cases where there is merit in doing this (specifically for cycling safety or bus priority at intersections), a successful congestion pricing system should enable all traffic to flow efficiently, including buses, and will improve conditions for all modes on the roads. Some advocates for congestion pricing see it as a tool to penalise driving and to make it more difficult for motorists to drive. If this is the policy adopted, it will be rejected by the public (as it has been in many many cities), as pricing need not be a tool of penalty, but a tool to make existing networks work better.

- Don't play with technology yet. There would be nothing wrong in eventually linking the current eRUC telematics systems to congestion pricing so their users (almost all commercial vehicles) pay charges automatically, alongside RUC. However, ANPR is just fine for now.

- Don't make any announcements on details until you have decided on most of them, and have responses as to why you made certain decisions. Don't let the media and public discourse determine policy. Design a good system with defensible policies, and then present it to the media and public, so you can make clear what might be negotiable and what is not. A litany of failures elsewhere are due to letting policy debates get out of control, raising fears and uncertainty, and consigning the concept to the "too hard" basket.

Monday 30 October 2023

Iceland likely to be first European country to introduce RUC for light vehicles

Few remember Iceland when discussing experience in road user charging (RUC) in Europe, perhaps because it is an island (and so has virtually no foreign vehicles visiting), and it is also not a member of the European Union (but then neither are Switzerland or Norway).

Iceland has had for many years a RUC for heavy vehicles, in the form of a fairly simple weight-distance charge on vehicles with a maximum allowable mass of ten tons or greater. In 2008, it raised IKK1.083b (US$7.8m).

RUC for EVs and plug-in hybrid vehicles

However, Iceland is about to leap ahead of all other European countries in being the first to implement a nationwide distance-based RUC for electric, plug-in hybrid and hydrogen vehicles from 1 January 2024. Consultation on a draft Bill (Icelandic only) to implement this charge has recently closed. Iceland Monitor reports that the fee will be ISK6 per km for electric and hydrogen powered vehicles (US$0.043 per km or US$0.069 per mile), but hybrids will be charged only ISK2 per km (US$0.014 per km or US$0.022 per mile), to reflect that they continue to pay fuel taxes.

Iceland has had a significant growth in electric and hybrid vehicles, with 85% of new light vehicles sold in Iceland in 2022 being electric or plug-in hybrids. This reflects a VAT exemption for such vehicles, and other very low taxes. 73% of Iceland's electricity comes from hydro-power and almost 27% from geothermal energy, so electricity prices in Iceland are immune from international commodity prices. Nearly 20% of all cars in Iceland are either electric or hybrid of some form, so the impacts on fuel tax revenues have been considerable.

So Iceland will have surpassed the rest of Europe as no European country has so far mandated or even agreed to introduce some form of distance-based RUC for any light vehicles at all.

RUC for all vehicles

This isn't the end, as the Icelandic budget indicated that the introduction of the new fee will be monitored in 2024 with an eye to applying it to ALL vehicles under ten tons, and to review the future of taxation of petrol and diesel. This had led to speculation that Iceland could put all vehicles on RUC and reduce or abolish fuel taxes used to fund the transport system. If it does so, then it will be a world-leader in transitioning from fuel taxes towards RUC, and so shifting from taxing energy to taxing road use.

Thursday 26 October 2023

Reactions in Singapore to ERP 2.0

Following the announcement of the roll-out of ERP 2.0 in Singapore (using GNSS-based On Board Units for congestion pricing), there has been some comment in the media in Singapore about the new system and policy around it. Some of this is likely to be relevant to other jurisdictions considering mandating such technology into motor vehicles.

What do motorists and car dealers think?

The Straits Times published an article on 25 October by Lee Nian Tjoe on what motorists and car dealers think.

Dealerships generally said that they were ready for the rollout, as some had been establishing how to conceal wiring and have the equipment installed in their vehicles, but some still were awaiting information...

Ms Tracy Teo, marketing director of Komoco Motors, which represents Hyundai, Jeep, Ferrari, Maserati and Alfa Romeo in Singapore, said the company is awaiting information and instruction from LTA on the next steps.

One of the key issues is that getting such equipment installed in a wide variety of makes and models may present challenges for some varieties of vehicles.

Comments from members of the public approached by the journalist were largely questioning with some concerns, such as the location of the OBU on the side of the passenger footwell. One objected to the system having capability to have stored value cards inserted given how technology had moved beyond that.

The article describes how a fleet operator was used to test installation of 500 devices in a pilot.

Should it have been rolled out in the first place?

A second article from the website Techgoondu is critical of the new system.

Author Alfred Siew describes it as:

the unwanted rollout of a costly project that has taken nearly 20 years to complete, if you count its early efforts. It is clearly outdated and inconvenient for users. Many questions have already been raised about this “next-gen” ERP 2.0 unit when it was unveiled two years ago. Most damning was why it was even necessary.

Part of this is unfair, as it is not a 20 year long project, but it is certainly was being thought about 10 years ago. Singapore needed a new system because "ERP 1.0" was creaky and obsolete, and needed replacement. It would have been cheaper to go all ANPR (Automatic Number Plate Recognition) based, but certain features would not have been available, and it could have simply been an update of the current technology. However, Siew notes correctly that the "next-generation" features around traffic information are largely available through apps such as Waze. Smartphones are able to be used as the in-vehicle display is optional, so the question becomes what it would have taken to make smartphones work? The key issues around reliability and linking it to the vehicle remain, but this is being trialled in Brussels now.

Siew describes the system as old technology, with the stored-value cards which are increasingly obsolete and an in-vehicle display reminiscent of pre-smartphone navigation systems. Of course many cars have automaker installed telematics with some key elements of the ERP 2.0 system included, although not available for congestion pricing applications. Making Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) telematics systems available and suitable for road pricing is perhaps the "rosetta stone" for ubiquitous road pricing in the future. Unfortunately efforts to do this so far have been very limited across the globe.

Siew finally criticises it for being a system with the capability to introduce distance based charging, but that capability is not to be used as of yet. That doesn't mean that it won't be and it is entirely understandable that a policy decision to do that would not be announced until the entire system is installed and proven, but unless it is used, it seems like an expensive solution to what is just an effort to replace an old system with one with less intrusive roadside infrastructure.

Of course LTA had signed the contract for the ERP 2.0 system some years ago and became committed to the project, so it had to be rolled out. Hopefully it will all prove to be worthwhile and operate successfully for many years to come.

Distance-based pricing is unlikely anytime soon

Newspaper Today online published an article by Loraine Lee on 25 October saying that it was unlikely LTA would implement distance based pricing soon.

Key issues identified were:

- How to apply it equitably, including the future of fuel taxes and vehicle registration/ownership taxes, so that those that travel the most are not paying disproportionately compared to what they do now.

- Questions over the location accuracy of the technology in parts of Singapore with tall building, and with tunnels (the latter is not a real issue, as systems elsewhere can clearly note when vehicles travelling on a road disappear and reappear at another location, that they must have been in the tunnel on that route).

- Need to consider the wider impacts of a shift towards distance-based charging on some road users.

- Purpose built OBUs for professional installation in vehicles

- Scaled down "self-installed" OBUs

- OEM telematics

- Smartphones

Wednesday 25 October 2023

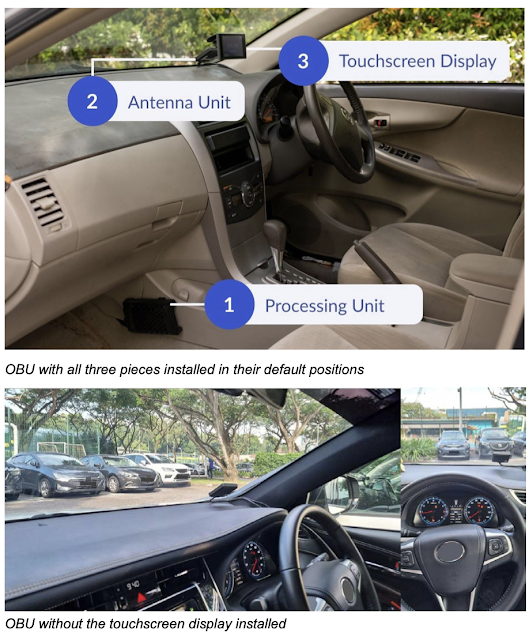

Singapore launches ERP 2.0... finally

The Straits Times reports that Singapore has, finally, announced to roll out of its ERP 2.0 On Board Units (OBUs) over then next two years. Starting in November 2023, fleet operators will get OBUs installed in their vehicles, and from no later than April 2024, new vehicles will have the new OBUs installed. Remaining vehicles in Singapore will be required to have the OBU installed based on date of registration over the subsequent two years.

Installation is estimated to take three hours for a car. All motor vehicles in Singapore will be required to have the new OBUs, including motorcycles (which have a smaller single unit OBU). Installation will be free of charge if done within a two month window specified by the Land Transport Authority (LTA) (notified to the registered vehicle owner in advance).

Payment options will remain the same including direct debit of credit or debit cards, or use of prepaid stored value cards (which can be inserted into the base unit of the OBU).

The car unit is in three components:

- Processing Unit

- Antenna Unit

- Touchscreen Display

|

| Singapore ERP 2.0 OBU for cars |

- Security for real-time charging transactions from prepaid stored value cards

- Reliability, given the range of smartphone models and operating systems available (including older models)

- Concern over ensuring whether an app is functioning, the smartphone is sufficiently charged and is connected to the mobile network.

Friday 20 October 2023

Victoria (Australia’s) electric vehicle road user charge ruled unconstitutional

In a landmark court decision, the High Court of Australia ruled (in a narrow 4-3 ruling) in the case of Vanderstock & Anor v State of Victoria, that the Zero and Low Emission Vehicle Distance-based Charge Act 2021 is invalid under Section 90 of the Constitution as it imposes a duty of excise. The charge was known as the ZEV in Victoria.

This effectively means Victoria’s distance-based road user charge (RUC) for battery-electric and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles is illegal. The basis for the decision is interesting, as it appears to be that:

The charge was deemed by the court to be “a tax on goods because there is a close relation between the tax and the use of ZLEVs, and the tax affects ZLEVs as articles of commerce, including because of its tendency to affect demand for ZLEVs”.

If I put my legal hat on (I am a lawyer), this is quite an interpretation, as it seems to regard the charge as being an excise because it affects demand for zero and low emission vehicles. This blog is not the place to debate the legal arguments, indeed the dissenting judgments amply raise the key issues.

The obvious policy question is if a charge of A$0.028 per km on the use of zero emission vehicles is an excise because of its "tendency to affect demand for ZLEVs”, and if the tax (it was critical that it be deemed a tax, and not a fee for services) is a tax on goods, is not the annual registration fee (which is A$876.90 (US$553) for a car in a metro area of Victoria) similar? It is effectively a tax on being able to use the car.

However, the court has ruled, and it does beg a wide range of questions both at the strategic policy level around charging road vehicles to use roads in Australia, and the effect the decision has on the options to do this. At a basic level there are two points:

1. The Victorian ZLEV tax as it was designed is unconstitutional: This was a mandatory charge, that had no option (as applies in some states in the US) to pay a flat annual fee instead, which only applies to a small proportion of light vehicles. Would a tax that had another option be legal? Would a tax that applied to all light vehicles be legal, including one that might largely replace registration fees (so may have a neutral effect on demand for light vehicles as a “good”)? Would it have been legal had the Department levied it as a fee based on costs of providing a service, rather than as a tax?

2. The Commonwealth can levy a tax charge such as the ZLEV, but only across all of Australia: If it were policy, the Commonwealth could pass legislation requiring all electric vehicles in Australia to pay a per km RUC. Similarly, could it apply it to all light duty vehicles? Arguably fuel excise duty does that now, but fuel excise duty strictly speaking affects demand for the fuels that are taxed, if you consider the definition applied by the High Court.

What happens next is obviously going to be a matter for the Victorian Government to consider, and indeed given both New South Wales and Western Australia have legislated for their own RUC systems to apply to electric vehicles from 2027, they will have an interest (along with all other States and Territories). Is it possible for them to design a road user fee, based on provision of a service (roads as a service) and the costs of providing it? If so, how could that be legally drafted without simply empowering a road manager to implement such a fee? Could it be applied across all road managers in Victoria? There are 79 local road managers and at least 1 state road manager in Victoria.

Victorian Premier Tim Pallas argued that it was about “fairness” and noted that electric vehicles were heavier and contributed more to “road degradation”. That latter point is highly questionable, but also not really relevant. The difference in weight between types of light vehicles makes very little impact on road wear, as most road wear and tear arises from the effects of weather and temperature, and the passage of heavy vehicles, not vehicles weighing < 4.5 tonnes.

The Commonwealth Government might be expected to have a view on the future of charging electric and other light vehicles for road use, as it was supportive of the plaintiffs. It would be reasonable to expect a policy position to be expressed in the coming months either to advance investigations in how RUC might be implemented for electric vehicles across Australia or to defer considering it until they are a larger proportion of the fleet. Ultimately it cannot be avoided, and it is in Australia’s interests to have a single coherent strategy to charging vehicles for using the roads, as it affects the sustainability and future of fuel excise duty. I hope that decisions are made in coming months for the Commonwealth to investigate pathways towards transitioning how light vehicles pay to use the roads, and alongside that, how revenue collected from them can be managed and efficiently distributed.

It's important to note that the Commonwealth already has a clear role regarding how heavy vehicles are charged for road use. Part of fuel excise duty is legally called a Road User Charge, which is what heavy vehicle pay to use the roads. Owners of such vehicles are entitled to refunds of the remainder of fuel excise duty when being driven on public roads (and to receive a full refund when driven off public roads). The Commonwealth has already been piloting options for a long-term transition from fuel excise duty and (State and Territory collected) registration fees towards paying by distance and weight. There is already some knowledge and understanding of the relevant issues within the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Culture, and the Arts (DITRDCA).

Could States and Territories design a RUC that is not illegal?

It might be theoretically possible to design a light-vehicle RUC at the State and Territory level that does not come within the definition of excise, as indicated in Vanderstock & Anor v State of Victoria. Some of the characteristics of such a fee could include:

- It is a fee based on consumption of a service, not a tax. This affects how it is collected and how it is enforced.

- A fee that replaces another charge (aiming to be revenue neutral), such as replacement of registration fees. Arguably this would not affect demand for the “good” if it replaces a different type of tax.

- A fee that applies to all types of (light) vehicles, which is also a replacement of registration fees, so it does not affect demand for one type of vehicle.

- A fee that does not apply to consumption out-of-state. Victoria's tax applied to distance travelled anywhere on public roads, making it more difficult to claim that it was about consumption.

I suspect States and Territories might investigate such options, if they are determined to implement a form of RUC, but there may be a preference to simply leave it to the Commonwealth. Motorists are likely to prefer this, but the political will to do it will depend on one government taking a chance (and needing to work with the State and Territory Governments, all of which control motor vehicle registers essential to making it work), rather than eight separate entities doing so.

What does the Commonwealth need to consider?

Clearly the basis for having the Commonwealth proceed is that it is Commonwealth revenue being eroded by changes in vehicle technology. Given work already underway investigating RUC for heavy vehicles, it would make some sense to have a unified approach, which co-ordinates with States and Territories.

A wide range of issues would need to be considered including:

• What types of vehicles should first be moved onto RUC? Just those that pay nothing now (EVs), those that pay significantly less fuel tax (PHEVs and BEVs) or allow any light vehicles to opt into RUC?

• What would be the best basis for rate-setting? Should it be based on cost-allocation on a forward-looking cost base as has been proposed for heavy vehicles?

• Would it (and if so when would it) apply to vehicles currently paying fuel-excise and if so, how would fuel-excise be treated (i.e., refunded, credited to a RUC account)?

• What technical solutions would be suitable? Automated options require equipment to be installed or existing telematics to be used, manual options require verification.

• Will technical solutions be piloted with a section of the public (as is being done for heavy vehicles)? What would be the purpose of piloting RUC?

• Will revenues be hypothecated into a roads fund? If so, how would revenues be distributed among States and Territories compared to existing Commonwealth funding for roads?

• Would a Commonwealth RUC be applied at a single rate regardless of State or Territory, or have rates set that vary by location? A location based RUC would limit the technical options that would be feasible.

• What entities would be responsible for operation and enforcement of a Commonwealth RUC? How would a high standard of customer service be ensured?

• What roles would States and Territories have with a Commonwealth RUC?

What now?

Regardless of what happens, there would need to be a significant Commonwealth role in any case. It would be costly and complicated to have potentially eight different RUC systems, all of which are focused on collecting data and money from vehicle owners in their own borders, and to enforce RUC across them. It may have been less problematic for some (Tasmania, Western Australia and the Northern Territory all have low levels of cross border traffic), but much more complex along the eastern states and territory.

Given States and Territories have generally made EVs exempt from registration fees and are unlikely to want to apply RUC more generally across all light vehicles, it seems likely they will now turn to the Commonwealth to get some direction around how it wants to approach RUC for EVs and RUC more generally. This is an opportunity to consider the wider road charging and funding framework across Australia, including the role of fuel excise and registration fees. RUC is inevitable for highly fuel-efficient vehicles, the question is not if, but when, but it should be considered within the wider context of the questions outlined above.

With three US states having implemented RUC for parts of their light-vehicle fleets already (Oregon, Utah, and Virginia) and a fourth having mandated it (Hawaii), and multiple others piloting and investigating it (including the Federal Government), there is extensive experience in addressing many of these issues. New Zealand’s long standing RUC system will soon be extended to electric vehicles (it already covers all heavy vehicles, and all light diesel vehicles) also provides some useful lessons. There are also several pilots that have been undertaken in Europe.

The Commonwealth Government may not decide to do anything in the meantime, but that is a policy choice, and it could be undertaken with the clear message that it is intended to encourage growth in EVs and PHEVs. However, the easiest time to introduce a RUC is when the vehicles it is meant to apply to are few, and technical and policy options to do so can be easy to test. Australia has time to develop a strategy for road charging that might place both heavy and light vehicles within a single framework. It would be wise to do so over the next few years, and take the chance to bring States, Territories, stakeholders and most importantly, the public with it.

Monday 11 September 2023

Cambridge cancels congestion charging and it isn't a surprise

I wrote in March 2023 about Cambridge's ambitious proposal for what it was calling a "Sustainable Travel Zone", but which was actually a congestion charge, and how it was not going well.

Well the BBC has reported that it has been cancelled, less than two weeks after revised plans were suggested that ought to have been the original plans in the first place.

I criticised the original proposal because its scale and scope were too ambitious, and because it offered little for those who would pay, as it was primarily designed as a revenue raising scheme, which had its scope defined by the amount of money local politicians wanted to raise to uplift the quality of its bus service. £50 million was to be spent enhancing services.

As a revenue raising scheme that was also described as being intended to "reduce traffic" it is hardly surprising that those who faced paying didn't see what they would benefit from, especially as few could envisage how the proposed improvements to bus services were "better" than their own cars, and there was next to no effort made to sell the proposal on the basis that it might improve travel times for those who still drive.

From that objective came a scheme design that was blunt and ill-focused. Why?

- It was designed as an area charge, like central London's congestion charge, so there could only be a single charge per day regardless of how much driving was undertaken. Those who undertook a single trip would pay the same as those driving commercially throughout the day.

- The area charge encompassed ALL of Cambridge. It effectively made the entire city into a congestion charge zone, regardless of how busy any streets were at any time, it priced the city for access, so those who drove towards the central city (who likely had other transport options for their trip) paid the same as those crossing from one side to the other (which would typically involve a less direct public transport trip).

- The charge would apply all day, from 0700-1900. So there was no effort to focus on peak charging at all, or focus on congestion. Although it would initially only apply in the AM peak in 2025 to commercial vehicles it would expand to all day operation from 2027 for all vehicles that would not be exempt.

- HGVs would pay exponentially more than cars, at £50 per day (perhaps £25 if zero emission) compared to £5 for cars. It's unclear how Cambridge expected to function effectively by treating HGVs as if they take up 10x the road space of cars (and have no modal substitute) when they actually take up 2.5-3x the road space of cars.

- What travel time savings and improvements in trip reliability will the system be designed to achieve?

- Can some of the revenue be used to improve the road network, whether by addressing deferred maintenance or improving some bottlenecks or safety issues in the network?

|

| Cambridge |